Wenak ya Allah — Where are you, God, amidst genocide?

By, Nathan Samayo, Ph.D. Student, Princeton Theological Seminary

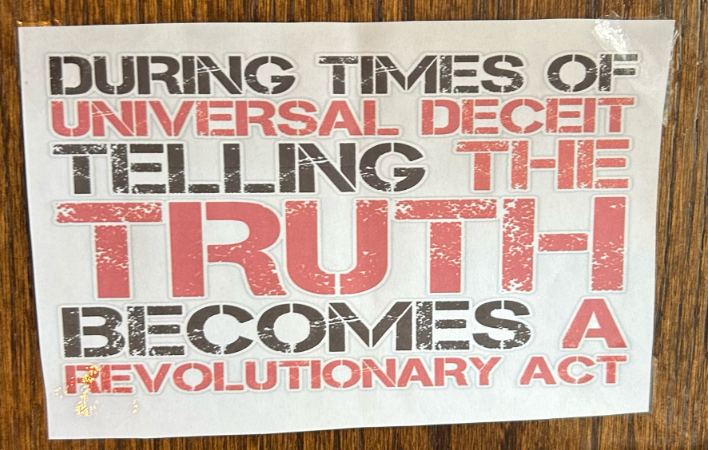

Sticker found at The Gateway Café, Old City Jerusalem

I am currently on my way to the airport in Amman, Jordan for the January 2026 Sabeel delegation to Jerusalem and the West Bank. I read “Gaza and Guatemala: Enfleshed Divinity in Women’s Ethics of Care,” written by a good from of mine from Nazareth. In the essay, my friend poses the question: Wenak ya Allah—Where are you, God, amidst genocide?

While the U.S. and Israel exercise the familiar mechanisms of state-operated genocide—executions, kidnapping and disappearance, sexual violence, counterinsurgencies—another tactic of genocide that often goes unnoticed under the “specter of physical violence” is the destruction of social fabrics and collective psychology. Genocides can destroy the “sense of community” where mass pain and suffering incites overwhelming feelings of helplessness, shame, guilt, and loss of control, especially in moments when people are unable to protect their loved ones. This can lead to hopelessness, isolation, and the loss of motivation.

This reality challenges Christians theologically. For Christians with humanitarian sensibilities and desires for “social justice,” theological narratives of liberation can often dismiss honest confrontations with horrific realities. I’ve noticed that Christians have a hard time sitting with the question: if God is with the oppressed, where is God in the genocide?

It is easy to quote Munther Isaac and say “God is in the rubble.” What does that actually mean? I don’t ask that question rhetorically. I also don’t ask that question because I disagree with Munther Isaac, nor do I believe that Munther Isaac asked that question uncritically (obviously he is very theologically informed). What I’m talking about here is how such theological claims often get appropriated by Christians—especially those with humanitarian sensibilities and the inability to sit in the “uncomfortable”—giving them quick theological justifications to explain horrific realities that lay in front of us, rather than doing the deeper, theological and practical work to attend to those horrific realities.

But my Palestinian friend points us into another direction, one that sheds light on the practices of remembrance and caretaking that Palestinian and Mayan women practice in the midst of genocide; practices confront reality. Under genocidal violence in Gaza and Guatemala, particularly sexual violence which strips women of their dignity, forcing them to deal with shame and alienation in secrecy, women have taken on the practices of remembrance and care for the well-being of their kin: restoring the remnants of their relatives; offering dignified burials; seeking justice through the legal system for crimes against humanity, when possible. These practices reknit social fabrics, collective psychology and the “sense of community.” These practices sit at the intersection of agency and victimhood, creating new spaces that nurture life to the best of their abilities.

I leave us with a quote to reflect on: “while theologians connect resurrection to the cross, I assert that liberation is not a predetermined event following suffering. The aftermath of genocide in Guatemala has not brought total liberation or justice, and the genocide in Gaza continues. Highlighting the invisible work of care and leadership embodied by Guatemalan and Gazan women exposes glimpses of the divine in our world, where God works in and through the violence that lays before us” (from Gaza and Guatemala).

Nathan Samayo is a PhD Student at Princeton Theological Seminary studying Indigenous religion and politics surrounding issues of climate change in the Pacific.